Dr. Andrew is an experienced and skilled trial witness. Complex medical issues are presented in terms easily followed and understood.

“Now Doctor, you did not actually perform this autopsy, did you?”

Opposing counsel unleashes the question, fairly dripping with contempt.

“No.”

“Would agree with me that the person best positioned to observe the pertinent findings in this case is the person who performed the autopsy?”

The dagger is aimed at the heart of the hired gun who would dare challenge the opinions of the autopsy pathologist.

“Yes.”

While this little charade is part and parcel of the majority of cross-examinations of forensic pathology consultants, it rarely gains purchase with discerning jurors.

The attorney proffering the expert in question can easily mitigate this nonsense by making sure the jury understands the thoroughness of the consultant’s evaluation of the case – provided, of course, that the pathologist has been thorough.

The reviewing pathologist should insist on seeing, at a minimum, every report, photographic and radiological image, statement, etc., that the autopsy pathologist has seen.

In some cases, the consultant may ask for more, e.g. past medical records. Certainly the autopsy pathologist’s narrative report should be reviewed along with any preserved bench notes.

One of the main purposes of generating a detailed autopsy report, including the production of images of pertinent positive and negative findings is so that another pathologist may indeed evaluate the case as if they themselves had conducted the examination. This is a crucial aspect of the scientific method and exposes the fallacy of the attorney’s shocking revelation the consultant did not do the original examination.

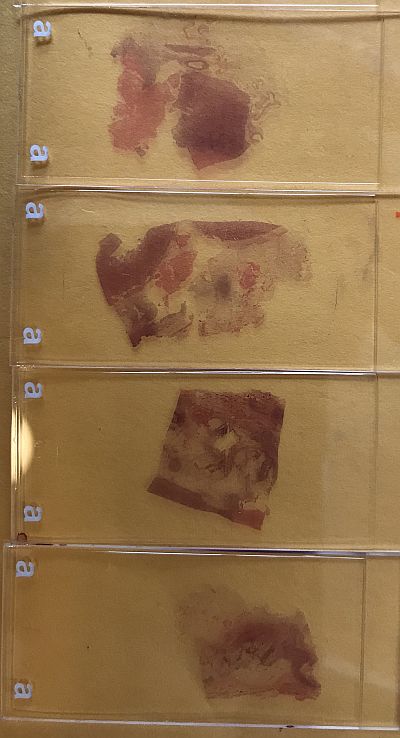

If histological slides were produced in association with the autopsy, the reviewing pathologist must examine recuts of the original slides or the originals themselves. Any insinuation by opposing counsel that the consultant was “not seeing the same thing” as the autopsy pathologist is specious. Histological slides are generated from tissue samples obtained at autopsy. The sample is cut to about the thickness of a nickel and is small enough to fit without crowding into a small plastic cassette. The cassette is filled with paraffin, encasing the sample.

The paraffin-embedded tissue is thinly shaved on an instrument called a microtome to a thickness of 4-10 micrometers (0.000156 to 0.00039 inch), then stained and mounted on a glass slide for viewing under the microscope. At these thicknesses, the chances of seeing something on one slide and not another from the same block of tissue is vanishingly low.

In summary, a competent, diligent forensic pathology consultant should be able to easily handle misleading questions regarding the basis of his or her opinion regarding examination of the evidence in a case. Two competent, experienced forensic pathologists can have differing opinions regarding the same data set. Whether one or the other is compelling is up to the trier of fact. If, on the other hand, the original examination is poorly documented, inadequately sampled or imaged, this is fair game for critique and opens a door for a broader range of interpretations of the data.