Where to begin on this difficult and sensitive topic? There are many myths surrounding organ and tissue donation, but the reality is the need for such anatomical gifts remains very high and many people benefit from them daily. The forensic pathologist is not infrequently confronted with this issue when the organ and tissue procurement agency in their jurisdiction approaches with a request to obtain organs from a possible homicide victim or other case falling under coroner or medical examiner jurisdiction who is on life support, but who has or will be pronounced brain dead. A request for specific tissues may come after death, even when organs can no longer be procured.

In the past, the reflexive response to such requests was to deny them. “This is a medico-legal case and these procedures will obscure accurate autopsy results.” Even if the forensic pathologist agreed to organ and/or tissue procurement, occasionally uneducated prosecuting attorneys, knowing next to nothing about forensic pathology or medicine would “forbid” these procedures “in the interest of justice.” Well, justice is in the eye of the beholder, no? Is it just to deny a dying person an organ needed to save their life in the misguided belief it will prevent a guilty person from being held accountable for their criminal actions? Is it just to consign people to blindness or heart failure by denying the postmortem procurement of corneas or heart valves because of a pending prosecution? Muckraking media pieces on pockets of corruption in the organ and tissue procurement industry have the potential to do more harm than good. Graft and malfeasance deserve to be exposed, but to taint the entire industry for the actions of a few seems to short-circuit justice as well.

The truth of the matter is that organ and tissue procurement agencies have evolved into being cooperative partners with the medico-legal authorities in their area. In some instances arrangements are made for the forensic pathologist to be present for the procurement process. More commonly, the procedure is thoroughly documented, including digital imaging. The agency report is made available to the forensic pathologist as well as the results of examination of procured tissues under the microscope. Residual tissue, for example heart tissue remaining after procurement of valves, may be returned to the forensic pathologist to conduct their own microscopical examination if deemed necessary. Defense counsel can hardly make the argument that the decedent’s heart, kidneys or liver was at the root of the “real” cause of death as opposed to the gunshot wound of the head, particularly if the heart, kidneys and liver are all working in living people in several different jurisdictions beyond that of death.

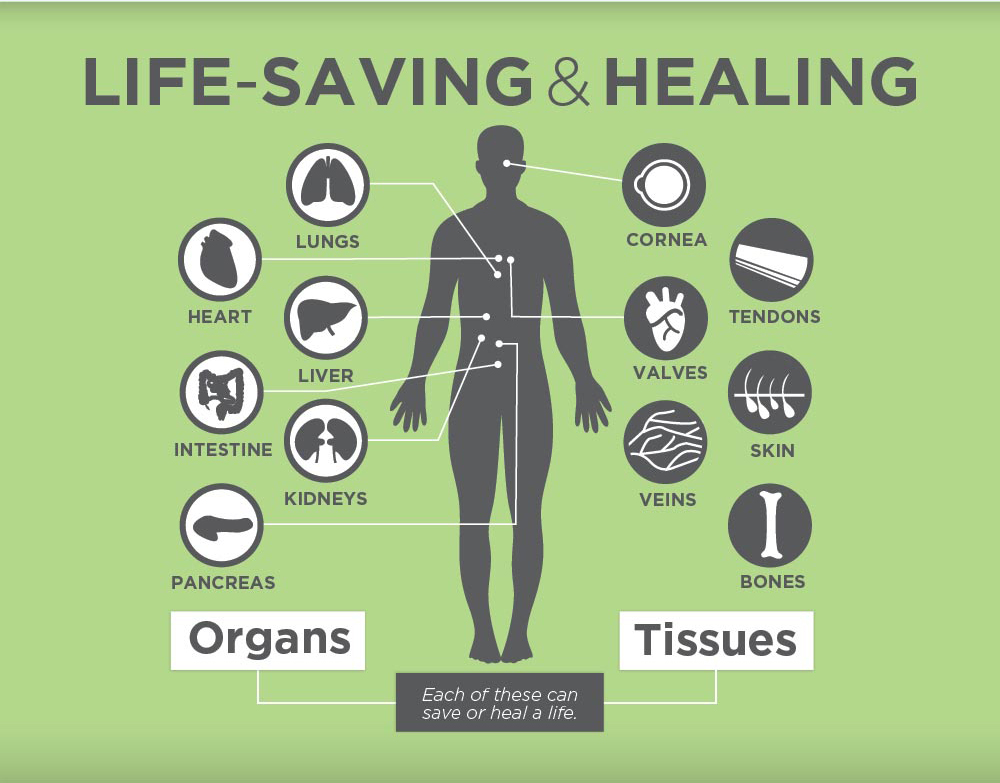

Credit: Infographic from Donate Life Life Banc

Likewise the claim that decedent was “alive” until they were killed by the organ procurement process is thankfully being seen far less often. The criteria for brain death are very stringent and a beating heart at the time of organ procurement being held up as evidence of life is specious and unscientific. The court may allow such an argument in the interest of providing the defendant all reasonable means to defend themselves, but it should be countered with strenuous vigor as it is simply untrue.

Lastly, a word about postmortem tissue procurement. This is a bit different than organ procurement and involves tissues that can be recovered up to 24 hours postmortem and still have the viability to allow transplantation. These tissues include, but are not limited to skin, heart valves, blood vessels, bone and corneas. They may be procured before or after the forensic autopsy. The latter may be deemed necessary if there are injuries, especially patterned injuries of the skin that may be of forensic significance. On the other hand, adequate imaging done by the procurement agency, usually defined by agreed upon protocols may meet the evidentiary needs of the forensic pathologist. Similar to organs, the procurement agency supplies the forensic pathologist with ample documentation, particularly where abnormalities are encountered.

No human system is perfect. I was personally involved in a case wherein I authorized the release of tissues prior to the autopsy. A pulmonary embolism was discovered during the procurement of heart valves. The thromboembolism was documented and placed in a container with formalin. Unfortunately, during the procurement of long bones from the legs, no clot was observed or even sought. The absence of a verified source of the pulmonary embolism led to a contentious debate during litigation over the wrongful death of the decedent. On the plus side, a meeting with the procurement agency resulted in changes in their protocols that would hopefully prevent a recurrence. We learn. We adjust.

In summary, thousands benefit from the graciousness of families and individuals who consent to organ and tissue donation. Perhaps you have done so yourself to be an organ donor as indicated on your driver’s license. Part of the public health role of forensic pathologists serving in the coroner and medical examiner jurisdictions in this country is to carefully weigh the benefits of authorizing procurement against the risk of losing vital evidence that could result in the prosecution of a guilty person. For this writer, the choice is quite easy. I shall always err on the side of life